Acts 3: 13-15, 17-19 (RM) or 12-19 (RCL); Psalm 4; 1 John 2:1-5a (RM) or 1 John 3:1-7 (RCL); Luke 24: 35-48 (RM) or 36b-48 (RCL.)

It’s a quirky little detail, nestled in the middle of a narrative in the process of building up momentum toward a remarkable climax: the revelation that this Jesus of Nazareth is alive to them. Not only is he real, but the Hebrew Scriptures and the prophets had foretold what had happened. The terror and tragedy of the past few days now begin to make some cloudy sort of sense to his friends.

“’Have you anything here to eat?’” It sounds too casual to be real. Here they are, barely comprehending what they’re seeing, talking to this, uh, familiar figure – and he suddenly asks them for something to eat?

“And they gave him a piece of broiled fish” as in the NRSV translation, or “baked fish” (in the U.S. RC Lectionary translation.) “Baked” sounds more plausible. Really, what would a first-century broiler look like?

“And he took it and ate in their presence.” He ate the fish. It went somewhere. The piece of fish disappeared. This was like the definitive proof that he was no phantom, no phantasm produced by collective hallucination.

This is typical of the Gospel of Luke where we find a total of ten meal stories. The previous meal story, in Luke 24: 13-35, shows this mystery figure who had walked alongside two puzzled disciples on the road to Emmaus, explaining how Scripture had predicted just these events that had shattered their world and their hopes. The disciples prevail on him to have supper and lodge with them, and while they were at supper, he took the bread … you know the rest. “Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him, and he vanished from their sight.”

Both of these stories read back the later Eucharistic meal practice of the Lukan church into the experiences of the first generation. These accounts of Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances are set in a template that included a Liturgy of the Word, a Liturgy of the Eucharist (at this time still called, more simply, “the breaking of the bread,”) and over it all, the living presence of the risen Christ. His presence was hard to recognize at first, and he disappeared shortly after recognition, but clearly our ancestors in faith in the first century knew for sure that the risen Christ was truly present in their assembly.

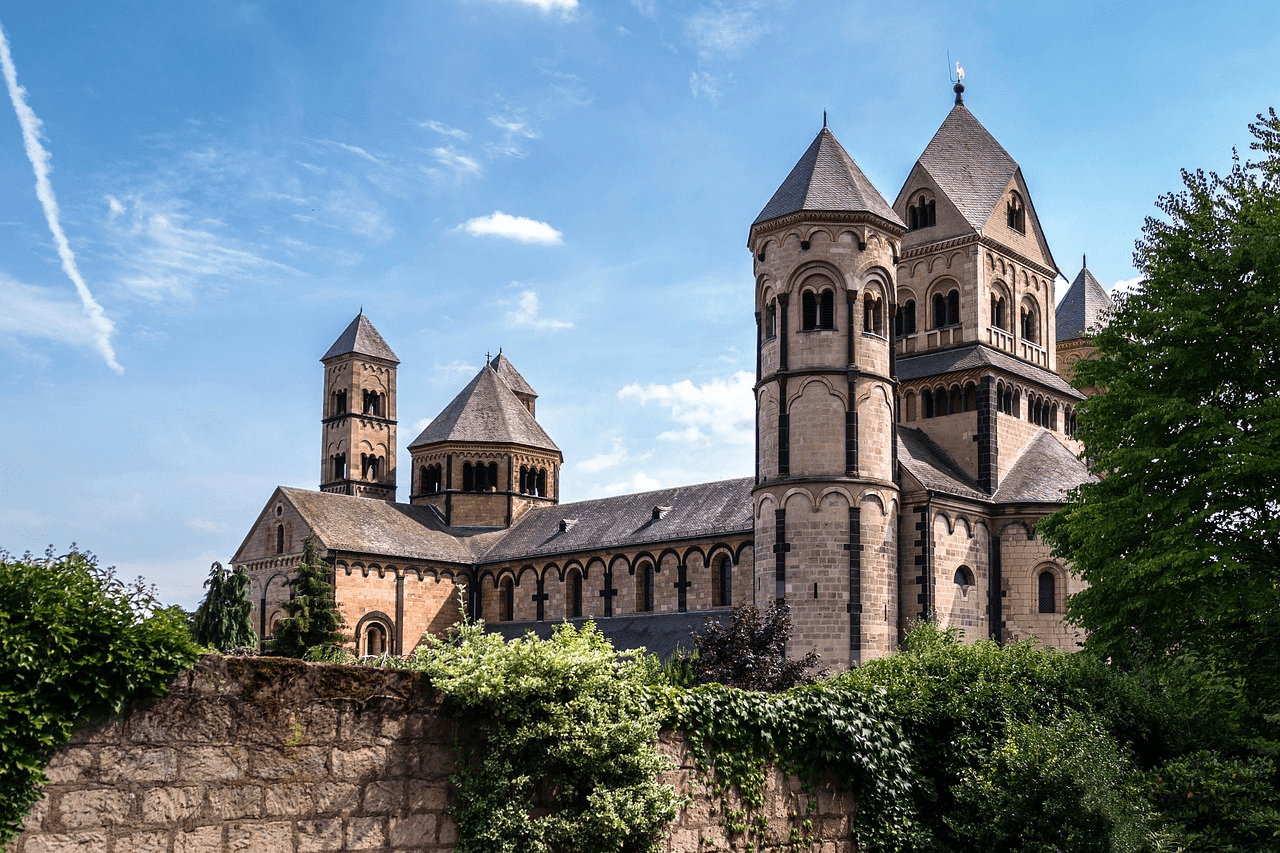

The Western church forgot that powerful truth for many hundreds of years. In the 1920’s a Benedictine monk named Odo Casel, of the German monastery of Maria Laach,* drew from his research on ancient Greek mystery cults to pose a striking and controversial thesis: that the real essence of the Eucharist, and any sacrament, consists in the living presence of the risen Christ, a presence that could not be imaginary, not perceptible through the bodily senses, but nonetheless real. It is not the priest but Christ who presides at every sacrament. The sacraments are Christ’s life among the baptized people of God who constitute his Body on this earth.

Casel came in for much sharp criticism in the 1920’s and ‘30’s due to his use of “pagan” sources — although in the 12th century Thomas Aquinas had done the same with Aristotle and was made to answer twice to charges of heresy. By 1947 when Pope Pius XII issued Mediator Dei, the Vatican magisterium was willing to grant, albeit grudgingly, the validity of this vibrant life-centred understanding of the sacraments. Mediator Dei however insists that this profound and dynamic theology of the sacraments must be credited, not to “newer authors” i.e. Casel, but to … Thomas Aquinas! As they say, you can’t make this up.

And the ”mystery presence” of Christ as the source and the holy power embodied in every conferral of every sacrament, entered RC official church teaching with the documents of Vatican II.

Odo Casel did not live to see his thought vindicated. He collapsed and died of a stroke shortly after intoning the Exultet at the Easter Vigil in 1948.

I used to tell my students, with a half-grin, that if you are a liturgist, and your time has come, you couldn’t stage your final exit any better than that.

© Susan K. Roll

*The monastery of Maria Laach was a centre of liturgical research and experimentation in the first decades of the 20th century. The first instance in modern times of the presiding priest turning around to face the people, and calling on the people to give the acolyte’s responses, took place here in 1920.

This Reflection has been lightly edited from that of April 18, 2021.

Susan Roll retired from the Faculty of Theology at Saint Paul University, Ottawa, in 2018, where she served as Director of the Sophia Research Centre. Her research and publications are centred in the fields of liturgy, sacraments, and feminist theology. She holds a Ph.D. from the Catholic University of Leuven (Louvain), Belgium, and has been involved with international academic societies in liturgy and theology, as well as university chaplaincy, Indigenous ministry and church reform projects.

Thanks for your reflections on Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances. This presence, that was “hard to recognize at first, and … disappeared shortly after recognition”.

With our ancestors in faith, may we all experience, and know for certain, the risen Christ, truly present among us.