Exodus 24: 3-8; Psalm 116; Hebrews 9: 11-15; Mark 14: 12-16, 22-26 (RM)

“So what’s wrong with magic?” asked Amy, a bright young philosophy-minded student, in the Sacraments of Initiation class. It took me a moment to catch my breath. She meant the question in earnest; she was more puzzled than sarcastic. I had just made a casual distinction between the words of consecration of the Eucharist as sacramental ritual blessing language, and “magic words.”

How do you articulate the distinction between sacraments and a magic ritual? How does the language used by theologians and church people not sound like wishful thinking – dying and rising with Christ in Baptism, being liberated from sin in Penance, receiving a commission through the laying-on of hands in Ordination, or healing through Anointing? And of course, on this Corpus Christi Sunday, the claim that in the blessing ritual at the altar the substance of bread and wine is changed into the body and blood of Christ, even though, in the words of Thomas Aquinas, physical “sense no change discerns?” And how do we teach these things to the young?

I’m thinking of an illustration in a German catechetical book for children that is still on the market. A photo of the tabernacle in the wall, above and to the right of the altar, is spread across two pages, with the title, “Here is where the Lord lives” (“Hier wohnt der Herr.”) In German “Herr” does not only mean master, boss, controller or lord, it is also the everyday word for “Mister.” Any adult male is called “Herr So-and-so.” And here is Mr. Lord, living in a box on the wall of the church. It’s hard to avoid thinking, “this is the faith that these children will leave behind some day.”

Have Catholics developed a tolerance, perhaps a blind spot, for the extraordinary idea that words plus stuff can change reality? What is the reality anyway?

It’s hard to argue with the words of Scripture attributed to Jesus at the Last Supper because they’re remarkably consistent across Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Paul’s second-hand account in I Corinthians. As written, there is no room for simile: “this is like my body,” nor for metaphor: “this is my body, so to speak.” The words lie flat on the page and brook no argument. Another indication of their likely authenticity, in addition to the consistency of the text witnesses, is their shocking, hideous character. In Jewish society of Jesus’ time, cannibalism was unthinkably revolting and so was drinking the lifeblood of any living being. Three evangelists and a later apostle were extremely unlikely to have made this up.

We may need to look elsewhere, to the very bodiliness of body and blood language itself. Christian theology anchors all sacraments in the Paschal Mystery – the suffering, death and resurrection of Christ – but before that is the Incarnation. When a child is enfleshed in the mother’s womb, the child is her flesh, her blood, nourished by her body’s resources, cushioned in her fluid. Do you remember the Frances Croake Frank poem from fifty years ago, “Did the woman say … ‘This is my body, this is my blood?’”

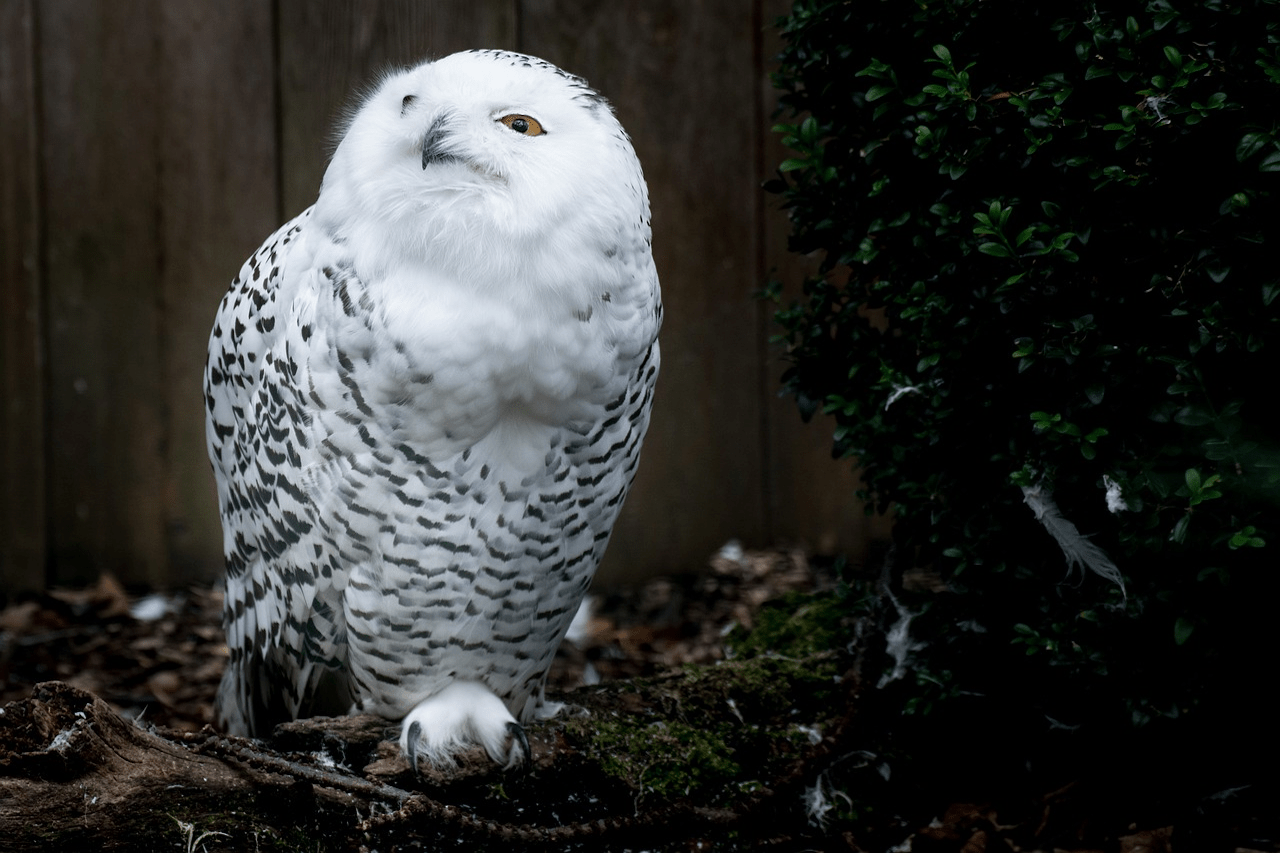

Precisely this “skin hunger” draws affectionate and living beings to each other – family members, friends, even people and their beloved pets. Just think of how profound is the idea that the living presence of God connects through living beings—not an abstract philosophical concept of a God, nor a distant overlord of the universe. Perhaps it is precisely in the delicacy and vulnerability of embodiment that the literal language makes sense beyond the words themselves.

If we sit at home in front of a laptop and see twenty-five squares on the flatscreen, each of the squares conveying a live camera image of someone’s face, plus an audio feed, does it create community? Enfleshed connection? It may well lead to a deeply cherished and much needed feeling of community, rather like a phone call from a friend or family member. But the electronic interface does not make magic. It does not change reality. There is no living, breathing, organic presence to each other. When we turn off the machine, or hang up the phone, there’s no one there.

Amy’s question about magic made an odd sort of sense. But it’s not Harry Potter’s sort of magic. It’s not what we do. It’s who we are. And who God is.

© Susan K. Roll

This is an edited version of the Reflection from June 6, 2021.

Susan Roll retired from the Faculty of Theology at Saint Paul University, Ottawa, in 2018, where she served as Director of the Sophia Research Centre. Her research and publications are centred in the fields of liturgy, sacraments, and feminist theology. She holds a Ph.D. from the Catholic University of Leuven (Louvain), Belgium, and has been involved with international academic societies in liturgy and theology, as well as university chaplaincy, Indigenous ministry and church reform projects.